Martha Holler '25 | A Little Black Book with Big Repercussions: How Jacques Goudstikker’s Personal Notebook Paved the Way for Nazi-Looted Art Restitution

Many people are familiar with Nazi Germany’s mass looting during World War II; however, the Allied powers' refusal to return looted goods in the post-War era is conveniently left out of retellings of world history. In the case of renowned Jewish art collector Jacques Goudstikker, Nazi Germany’s occupation of his home country, the Netherlands, left his valuable art collection vulnerable to the looting efforts headed by Hermann Göring. Jacques would not live to see the war’s end, leaving behind the only personal possession he brought with him when fleeing Amsterdam: his “Black Book.” When Jacques’s widowed wife sought the restitution of her family’s looted property, the Dutch government refused to acknowledge the collection’s forced “sale” to the Nazi party and instead retained ownership of the art for the government’s own museums. Over half a century after the initial looting of the Goudstikker collection, Jacques’s goddaughter would uncover the Black Book, setting into motion a new, ultimately successful, restitution claim for her family’s legacy. The Black Book’s integral role in the unprecedented victory of the Goudstikker restitution case has cemented its relevance in subsequent Holocaust-related restitution cases. The only personal item tying Goudstikker to his art collection that he brought with him when fleeing from Nazi occupation, the Black Book, has become a symbol of justice and triumph over both National Socialism and antisemitic government policies around the globe. Furthermore, in its grueling but ultimately successful use in the Goudstikker art restitution case, the Black Book has managed to preserve a large portion of the Jewish art community and culture prior to World War II.

Jacques’s Black Book is credited not only with restoring part of Goudstikker’s art collection, but also with preserving a glimpse into the vibrant pre-War Jewish art community and culture in Amsterdam. In a time when antisemitism seemed to infiltrate every political, social, and cultural sphere, Amsterdam stood out as a safe haven for Jews. The city started this tradition of tolerance during the Spanish Inquisition and has maintained it ever since. Because of Amsterdam’s commitment to religious tolerance, it has been given the affectionate nickname “Mokum,” a Yiddish word meaning “place.” The longevity of the nickname “Mokum,” “although only a fraction of Dutch Jews survived the Holocaust,” speaks to the lasting influence of Jewish culture on Amsterdam. Jacques’s extreme success is a testament to the opportunity available to Jews living in Mokum, as it was during his time in Amsterdam that Jacques became "the most important art dealer of his time." In the years prior to the outbreak of war, Jacques had become a revolutionary in his community; he was "distinguished as a cultural leader and pioneer who sought to enrich the lives not only of the privileged but of all art enthusiasts." It was in Mokum that Jacques had the opportunity to influence society and fully embrace his Jewish heritage.

Jacques's Black Book's ledger shows how his Jewish identity contributed to his success as a revolutionary art collector. Jacques entered an art market resistant to change, and he left it transformed. In the 1920s, the Netherlands was insistent on only showing the work of Dutch masters; its lack of diversity of artists was shocking. Jacques set out to change this, and from his Black Book records of the pieces he purchased and displayed, we know he was incredibly successful in doing so. Contemporary Dutch art director Henk van Os reflects on the impact Jacques Goudstikker had on Mokum, stating, "Between the two wars, Jacques Goudstikker was the man who brought the Dutch patriciate of the era into contact with prominent foreign art and, in so doing, greatly expanded their view of the art world." Jacques modernized museum collections previously stuck in the past, and, in doing so, he propelled Dutch art collections into dialogue with works from all over the world. This is largely credited to his Jewish identity, because, as a Dutch Jew, Jacques likely understood the complexities of the diaspora and, subsequently, the importance of internationality in a way that his other Dutch contemporaries could not. Jacques’s insistence on expanding the horizons of Dutch art was also likely instilled further by his family’s original residence in ‘s-Hertogenbosch, a city known for its great multiplicity of French and German culture.

Jacques’s Black Book is a testament to his fervent participation in family tradition. Jacques’s strong passion for art was curated by his family, who were also art dealers and aficionados. Dutch art historian Peter Sutton explains, “Their art dealing business was set up in Amsterdam by Jacques’s grandfather, Jacob Goudstikker, as early as 1845 and was carried on by his father, Eduard J. Goudstikker.” For Jacques, art dealing was the family business; however, Jacques quickly surpassed his familial predecessors and soon made a name for himself. Historian Peter Sutton claims, “Jacques officially entered his father’s business in 1919 and almost immediately introduced distinctive changes.” Upon carrying the torch of his father’s and grandfather’s legacy and finally being able to move the family business toward an international market, Jacques began diligently documenting his own sales and purchases of artwork in the form of a personal ledger, a small black notebook. For Jacques, this notebook of course served the pragmatic purpose of keeping his affairs in order, but it also had a symbolic purpose: it documented his excellence in his profession, a profession handed down to him by his elders. This small black notebook represented the continuation of his family’s legacy.

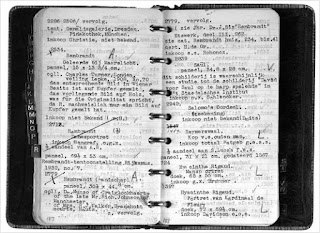

Despite the ledger’s unassuming appearance, Jacques’s Black Book would become the sole testament to Jacques and the Goudstikker family’s life’s work. As Jacques’s success grew, so did his meticulous entries into his Black Book. The book itself is unassuming; it is small, measuring in at 4.7-by-7-inches. Its outside is bound in plain black leather and bears no descriptive text. Its inside, however, holds the meticulous details of every piece of artwork bought and sold since Jacques joined the family business in 1919. Journalist Alan Riding describes with awe the painstakingly precise nature of the book’s logging system. He writes, “In alphabetical order by painter, this travel inventory lists 1,113 of the paintings Goudstikker left behind, with their titles, size, date of purchase, and, in code, the price paid for each.” Alan continues, “At the letter R, for instance, the names of Raphael, Rembrandt, Rubens, and van Ruisdael appear, while the letter D discloses Donatello and, several times, Van Dyck.” While Alan describes the diligence with which Jacques documented the pieces of his collection, he simultaneously shows the impressive size and range of the collection itself. Indeed, Jacques’s art taste was renowned, and his collection was beyond impressive. But it is thanks to the little Black Book, no larger than one’s own hand, that the Goudstikker’s cultural legacy has been preserved today.

It is the survival of Jacques’s Black Book that has preserved the Jewish influence he had on the Dutch art market, the story of his success, and his entire family’s legacy altogether. On May 10th, 1940, Nazi Germany invaded the Netherlands. On May 13th, Jacques, his wife, Dési, and their one-year-old son, Edo, fled Amsterdam. Jacques had been informed of the dangers of Nazi occupation by his friends in Austria. The information he received, coupled with “the anxiety spreading throughout the Jewish community in Amsterdam,” Jacques hastened to make plans for his family’s emigration. Jacques and his young family managed to find safe passage aboard the SS Bodegraven. They had left their entire lives behind, bringing with them only what they could carry. Of all the items in Jacques’s possession, he only brought one personal item: the Black Book. It was on this boat heading to South America that Jacques tragically fell in a ship hold and died. He was only 42 years old. Dési was left to carve out a new life for herself and her one-year-old child alone. She was given a small black notebook found on Jacques’s person. His personal ledger, the only belonging he dared take with him, now outlived him entirely.

As the newly widowed Dési struggled to emigrate abroad, the Goudstikker legacy was being looted back in Amsterdam. STAIR Galleries reports, "Hermann Göring... took approximately eight hundred of the most valuable works back to Germany, where they were displayed in several residences." As for "the gallery itself and Goudstikker's lavish country estate, they were transferred to Göring's henchman, Alois Miedl, in a forced sale at a fraction of their value." Goudstikker's life's work, his family's legacy, and his Jewish culture were stripped away as the Nazis plundered his gallery. After cross-listing suspected looted art with the surviving Black Book's catalog, it has been determined that "forced sale and looting of the Goudstikker Gallery is considered among the largest single acts of plundering by the Nazis." The theft of the Goudstikker gallery gave Jacques’s Black Book a whole new purpose, as it became the only evidence of his entire life’s work.

Unfortunately, the Nazis’s original plundering of their possessions would not be the last time the Goudstikker family was unjustly robbed. Dési ultimately settled in New York, and it was in post-War America that she engaged in “a bitter seven-year legal struggle, between 1946 and 1952… to try to regain as much she could of the family’s looted property.” In the words of Dési’s granddaughter, Charlène von Saher, Dési “confronted a restitution regime that did everything in its power to make it difficult for Jews to recover their property.” Journalist Alan Riding writes on the often self-serving approach the Allied powers took to art restitution in the post-War era. He states, "After the war, the Dutch government recovered around 400 of Goudstikker's paintings, some in Amsterdam, others returned from Germany by the victorious Allies. Dutch officials argued that they had been sold in good faith by Goudstikker's employees." A press release detailing the many attempts Dési made in her lifetime to reclaim her family's property sums up the result well. It reads, "Because of the wrongful resistance of the Dutch government, Dési was never able to resolve her claim to these artworks." The Dutch government's refusal to acknowledge the circumstances under which the Goudstikker collection was illegally sold off and looted allowed them to retain the paintings and hand them in their own museums. Nazi loot of Jewish lives now hung proudly in national galleries, while the descendants of these victims were met by government policies unconcerned with justice.

Dési was not the only person who experienced great difficulty in seeking post-War Holocaust restitution, as many restitutions began to give way to the trend of grueling legal battles at a high expense. A restitution attorney puts just how expensive these cases can be, stating, “I am almost at the point where I would say that if the art is worth less than $3 million, give up.” Other pillars in the restitution field have shared similar sentiments. If not deterred by taxing costs, one may falter when dealing with unhelpful museums that would rather drag out legal proceedings than hand over stolen artwork. Another lawyer known for his work with Holocaust restitution claims states, “While initially the museums indicate that they take our claims seriously and they will undertake an investigation, these situations have dragged on without any resolution.” Despite repeated advice to “give up” or not pursue restitution cases altogether, many descendants of Holocaust survivors respond with even more fervent determination to receive justice for their family. For them, the price of restitution is not monetary.

For many, the pursuit of restitution is a symbolic restitution of the family and loved ones lost to the Holocaust. A quote from two brothers seeking art restitution explains the deeply personal nature of Holocaust art recovery. The Goodman brothers explain, “The Degas was hanging on my grandmother’s drawing room wall, and she ended up in a gas chamber. I cannot let it go.” For the Goodmans, like many, restitution is not a choice; it is a need for family healing, mourning, and closure. These looted art pieces have become some of the only surviving evidence of Jewish culture and personal family heritage, the only proof that these people not only existed, but also lived. The Goudstikker family felt no differently, as for them, their family’s legacy and name had been broken and scattered across the globe. In this way, Jacques’s Black Book became a witness to the Goudstikker family’s heritage in a world that would rather let that heritage be forgotten.

Like many others seeking restitution, the Goudstikker family refused to give up due to the deeply personal and symbolic nature of Holocaust restitution. The Black Book remained in the family’s possession even after Dési’s death and, in the words of Charlène von Saher, “ultimately would be the key document we used to establish claims to Jacques’s collection.” Jacques’s meticulous ledger would become the evidence of ownership used to restore his renowned collection over half a century after its creation. Paintings believed to have been looted from Goudstikker’s gallery were cross-referenced to his Black Book, and, slowly, the ability to prove legal ownership and illegal sale of artwork was underway. One of the art researchers working on Goudstikker's restitution project, Jan Thomas Köhler, explains the precise and diligent work required in such legal cases. He writes, “We have to look for paintings one by one,” and in a case aiming to reclaim over 1,000 works, such a task can be daunting. It was through tedious research, the making of new claims, and countless rejections by state governments and museums that Charlène von Saher realized her family had “been robbed twice. Once by the Nazis and then by the Dutch government.” Ultimately, her family’s grueling pursuit of restitution would see a glimpse of justice in 2006 with the successful return of 200 Goudstikker paintings that had been held by the Dutch government post-World War II.

The impact of Jacques’s Black Book is not limited to the successful restitution of the Goudstikker family’s artwork; rather, the Black Book has made waves in legal procedures internationally. Throughout the course of the Goudstikker’s various claims against the Dutch government, publicity on Holocaust restitution gained traction. Soon, the public made it very clear where they stood on such matters. In response to the Goudstikker suit, the Dutch government created a Restitutions Committee in 2002. Thus, “numerous investigations launched by the Dutch government since then have confirmed that the Dutch state’s handling of post-War restitutions was cold and bureaucratic.” In a war of political attrition with the Dutch government, the Goudstikkers had won, and the implication of their win meant more hope for others seeking Holocaust restitution. The Black Book’s role in the Goudstikker case’s success paved the way for further Holocaust-related restitutions for other Jewish families, for many of whom these restituted pieces are the only surviving legacy of their heritage.

Through Goudstikker’s victory, Jacques’s Black Book has become a symbol of justice and triumph over both National Socialism and antisemitic government policies around the globe. The Black Book has preserved pieces of the Goudstikker’s family heritage threatened by Nazi Germany. It has been the preserver of memory, specifically of Jacques’s status as an acclaimed art collector and his participation in the larger Jewish community. Such things were desired to be wiped from the world’s memory by the Nazi regime; thus, the little Black Book’s legacy is one of resistance. Today, Jacques’s Black Book is still in the possession of the Goudstikker family, which occasionally lends it to various museums and traveling exhibits alongside some of the restituted paintings. As it travels, the Black Book is a “reminder of the tragic loss of life and identity that were the hallmark of the Holocaust.” Through the Goudstikker family’s generosity and partnership with the Contemporary Jewish Museum, the Black Book’s display continues to educate museum visitors about the deep and long-lasting effects of the Holocaust and the pervasive nature of antisemitism that still exists today.

Despite seeing success in the recovery of her family’s art, Jacques’s granddaughter, Charlène von Saher, is still haunted by the trauma of the losses her family has suffered, particularly those who did not live long enough to see justice prevail. Charlène still wrestles with the complicated mixed emotions she feels from the Black Book and the memory it preserves. She laments, “I think about the fact that my dad never saw any of his father’s art collection intact, and how justice seems to have skipped a couple of generations.” For her, the Black Book is a reminder of both great triumph and great loss. Ultimately, however, the Black Book serves as a constant call to action for Charlène. Both to continue the efforts of her family’s and other restitution cases, but also to appreciate and partake in the heritage she has recovered that her elders could not. She states further, “We hope that the restitution of this wonderful collection will lead governments, museums, and other institutions throughout the world to act just as responsibly and promptly and return all Nazi-looted art in their possession.” For Charlène and many other Jewish descendants of those victimized by Nazi Germany, such recovery of stolen belongings becomes fragments of a glimpse into the lives of those lost during the war and, thus, a glimpse into pre-War Jewish culture that has since been forever changed. Although he may not have known it then, when Jacques slipped his Black Book into his pocket before boarding the SS Bodegraven, he was truly bringing with him a piece of a historic, vibrant community, as well as a piece of his family’s legacy. Had it not been for the survival of the Black Book, this too would have been lost to the Nazis and erased from the world’s history. Instead, a small, unassuming, plain black notebook has managed to thwart several attempts to efface Jewish history and triumphantly lives on as a continual act of resistance to past and present antisemitism.

Bibliography:

Baker & McKenzie. "Goudstikker: 'At Long Last, Justice.'" News release. June 2, 2006. Accessed March 21, 2024. https://www.herrick.com/content/uploads/2016/01/2efac18113551a56d4d63417b1ff0e1e.pdf.

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. "'s-Hertogenbosch." Encyclopedia Britannica, June 25, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/place/s-Hertogenbosch.

The Contemporary Jewish Museum, and Ian Reeves. Gallery Photos: Reclaimed Paintings from the Collection of Jacques Goudstikker. October 29, 2010. Photograph. Accessed March 21, 2024. https://www.thecjm.org/exhibitions/36.

Henry, Marilyn, and The Jerusalem Post Ltd. "Recovering Looted Art: A Rich Man's Game." ProQuest. Last modified November 14, 2017. https://www.proquest.com/docview/319215667?sourcetype=Newspapers.

The Jewish Museum. Jacques Goudstikker's Black Inventory Notebook. Image. Jewish Museum. March 15, 2009. Accessed March 21, 2024. https://s3.amazonaws.com/tjmassets/exhibition_pdfs/Akte-38-Blackbook.pdf.

Lebovic, Matt. "Why Amsterdam's Beloved Nickname Is a Centuries-Old Yiddish Word, 'Mokum.'" The Times of Israel, March 25, 2018. Accessed May 7, 2024. https://www.timesofisrael.com/why-amsterdams-beloved-nickname-is-a-centuries-old-yiddish-word-mokum/.

Loeb, Jeanette. "The Jewish History of Amsterdam." Jewish History Amsterdam: Guided Tours in Jewish Amsterdam. Accessed May 7, 2024. https://jewishhistoryamsterdam.com/the-jewish-history-of-amsterdam/.

Opening Talk | Reclaimed: Paintings from the Collection of Jacques Goudstikker. Narrated by Charlène von Saher. Contemporary Jewish Museum, October 28, 2010. YouTube.

Riding, Alan. "Göring, Rembrandt and the Little Black Book." The New York Times (New York City, NY), March 26, 2006. Accessed March 21, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/03/26/arts/design/goring-rembrandt-and-the-little-black-book.html.

Stair Gallery & Auctions. "The Incredible Story of Dutch Art Dealer Jacques Goudstikker." Stair. Accessed March 21, 2024. https://www.stairgalleries.com/news-insights/insights/the-incredible-story-of-dutch-art-dealer-jacques-goudstikker/.

Sutton, Peter C., Bruce Museum, and Jewish Museum. Reclaimed: Paintings from the Collection of Jacques Goudstikker. Greenwich, Conn.: Bruce Museum, 2008.

VAN HAM Restitutions. "Jacques Goudstikker Collection." VAN HAM. Accessed May 7, 2024. https://www.van-ham.com/en/discover/van-ham-restitutions/jacques-goudstikker-collection.html.

Comments

Post a Comment